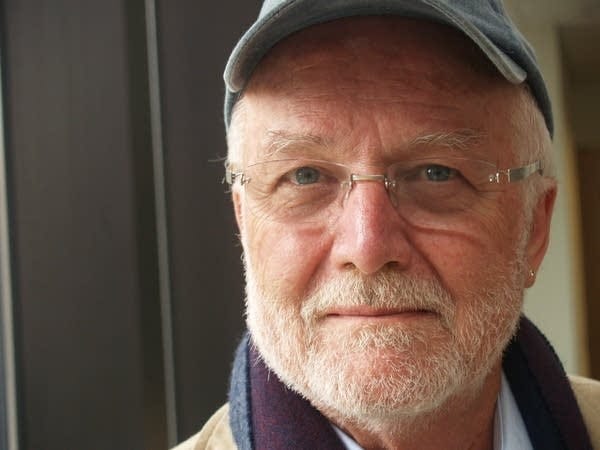

The Memory of Great American Writer Russell Banks Lives On Still

Author of "Cloudsplitter," "The Sweet Hereafter," "Continental Drift," and many other works, Banks has left an enduring literary legacy.

Note: You can watch a video version of this article here.

Without memory, how can we as individuals know who we are? And, perhaps more importantly, how can we as a society judge the merits and morals on which our society stands today? The novelist Russell Banks, who died last Saturday at the age of 82, made a life out of bearing witness to the forgotten, and of recording memory for the sake of survival itself.

In his many books, from the magisterial Cloudsplitter, a fictionalized account of the life of radical abolitionist John Brown, to the intimate but reserved family dramas of the Painter family in Success Stories, Banks gave beautiful, heartrendingly sad voices to common people and their everyday toils. He deftly revealed the pressure cooker existence that it is to live under American capitalism. And, like the best artists, he helped one to see, as only a storyteller can, the irreducible humanity that can never be driven out from even the worst monsters amongst us.

“It’s remarkable to me the degree to which, and the speed with which, memory gets lost in America,” Banks said in an interview with journalist Chris Hedges, “and perhaps elsewhere, wherever the world has now been so decentralized and where no one lives with anyone older than they are.”

The need to hold on to memory, to use the knowledge of the past self to give an accounting to the present self, if only, or perhaps most critically, to preserve the possibility of redemption in the private life, is a key motivating force that is suffused throughout Banks’ work. The storyteller in Cloudsplitter, Owen Brown, a real-life son of John Brown and one of the few who escaped the hangmen’s noose after the ill-fated raid at Harper’s Ferry, is imagined by Banks to finally tell his famous father’s story only after much deliberation on the utility of using memory as a bulwark against the ulterior motives of others who want to use the Brown family story for their own ends.

The importance of memory is not just in the grounding effect it has on individuals, but also in its ability to shatter atavistic myths, to pull back the dangerous veil of innocence with which we cover ourselves, to remind us of our bad debts, as it were, and to reveal to us, irrefutably and forever, that, as James Baldwin put it, “the bill is in.” Baldwin, having grown up in Harlem as a black man in an unforgiving country, understood dreadfully well the lies that this country tells about itself, and therefore also understood memory to be the rock which can — must — smash that deadly artifice. In his work The Evidence of Things Not Seen, Baldwin writes:

…nor, since [the West] believes in a history that is entirely its invention, does it have any sense of the dreadful tenacity of human memory, what that memory records, and how every bill must be paid…I can tell you not only that my soul is a witness, but that what goes around, comes around. A people who trust their history do not find themselves immobilized in it. The Western world is located somewhere between the Statue of Liberty and the pillar of salt.

In Banks’ Cloudsplitter, the character Owen Brown muses on the necessity for members of the white race to cleave to a truer sense of their dark history and to thereby separate themselves “from the luxurious unconsciousness,” itself a dangerous form of self-absolution, that guarantees the continued enslavement of blacks at the hands of white slavers and their irresolute liberal abettors. To accomplish this, in the radically evil days of American slavery, the white man, Banks writes, “has to be willing to lose his own history without gaining another. He will feel like a man waking at dawn in a village that was abandoned while he slept, all his kith and kin having departed during the night for another, better place in an unknown land far, far away. All the huts and houses are empty, the chimneys are cold, and the doors hang open.” The first step towards regaining one’s true memory, of reaching out for the shattering knowledge that gives us any hope of redemption, is a step into isolation from one’s own clan. John Brown, the steadfast martyr, knew this, and so did Russell Banks.

Though wincing at any attempt to box him into a rigid ideology, Banks’ particular worldview is nevertheless revealed by the troubled characters he chooses to highlight in his books — working-class stiffs, incorrigible but lovable alcoholics, unfaithful lovers, reluctant murderers, hardworking widows, bereaved parents, zealots, and, perhaps most controversially, the main character in Lost Memory of Skin, a young sex offender, stigmatized by society and relegated to a life of isolation, addiction, dislocation, and shame.

Banks himself grew up in relative poverty in New England, the eldest son of a single mother — his father, an alcoholic and violent man, abandoned the family when Banks was twelve years old.

By “lifting the rock on bourgeois respectability,” as Banks put it, by putting forth poetic visions of the lives of the underclass, his work skewers the soft underbelly of our mendacious capitalist order, an order which tells us that everyone gets what they deserve, an order which would rather have us forget the memory of a better life or the possibility of something different, and which says that the system we live under represents, in the words of Voltaire’s Master Pangloss, the best of all possible worlds. With a good reporter’s eye for truth and justice, not just the facts, as it were, Banks speaks in a language that is immediately understandable to anyone who actually works for a living, a language which is increasingly alien and vulgar to those comfortable careerists who do the dirty work of our oppressors, and a language which refuses to let memory die.

“I feel like I’m writing about the majority of human beings on this planet, more than a majority,” Banks said when pushing back against the notion that he only writes about outcasts. “My attention goes out to those people, and they are everywhere. And so whenever someone says, yes, you are writing about the outcasts and the minorities, it’s not true. There are more people of color than there are people without color on this planet.”

Alongside the primacy of memory, Banks speaks to the preciousness of community and how precarious our communities can become. In The Sweet Hereafter, a deadly school bus accident which caused the deaths of dozens of school children shakes the foundations of an entire town, turning families against one another as secrets are buried and a scapegoat for the tragedy is searched for. “All over town there were empty houses and trailers for sale that last winter had been homes with families in them,” observes the character Dolores, who was the driver of the bus. “A town needs its children, just as much and in the same ways as a family does. It comes undone without them, turns a community into a windblown scattering of isolated individuals.”

In eulogizing Banks, Cornel West wrote: “He is one of the last literary giants who brought together the great legacies of Herman Melville and Mark Twain, the ambitious epic reach and the delicate comic freeplay of our American achievements.”

I first discovered the writing of Russell Banks when I was a freshman in high school. On the book shelf in my English teacher’s classroom was an original hardbound copy of Banks’ collection of short stories called Success Stories. During open study time, I read the stories out of order, not realizing that, with recurring characters from the Painter family being given their own chapters concerning various stages of their lives, the book is meant to be read in order. My disjointed reading of the book nevertheless made a lasting impression on me. Success Stories, along with George Orwell’s 1984, are the two earliest works I discovered which mindblowingly gave words and voice to thoughts, feelings, and ideas which I myself had floating around vaguely in my mind but which I could never give proper formulation to. That is what the best writers do. They put things in just the right way and thus allow you to carry on those concepts more concretely inside yourself than ever before. Years later, I was lucky enough to find at a used book store another hardcover copy of Success Stories signed by Banks. Now seems like a good time to revisit it.

With the loss of Russell Banks, we have lost a library of memory, an artist who shined uncommon light on our common beauty, and a poet whose example must endure if we are to have any hope of reclamation in the face of the moral degradation of our time.

I’ll give the final word to Banks himself, leaving with a short piece from Success Stories called “Captions”:

Captions 1 Raising glassfuls of "home brew," Early and Dora Keep, the proud parents of the bride, toast the grateful parents of the groom, Roger ("Rog") and Estelle LaBas. Early is Catamount's trusted game warden, and Rog, proprietor of LaBas Hardware Co., is fondly remembered for his hilarious portrayal of the German shepherd in the Suncook Players' production last fall of the famous German comedy play, Dog Food. Their wives, Dora and Estelle, have long been active in community bake sales and bean suppers. This wedding joins not only two of Catamount High School's favorite members of the class of 1984, but two of our town's most popular families as well. Congratulations to all the Keeps and all of the Labases too! Congratula 2 In the background, next to the refrigerator, Charles ("Chuck") LaBas, the lucky groom, and Swenda Keep, now the lovely Mrs. LaBas, are about to cut their beautiful wedding cake, made and presented to the happy couple by the students of the Suncook Valley Cake Decorating School. Chuck played goalie for last year's Catamount High championship hockey team and is now employed as a line repairman for the Public Service Co. Swenda was the valedictorian of her 1984 class at CHS and since graduation has been student at the Suncook Valley Cake Decorating School. After their wedding trip to Maine, the happy couple plans to live in their new mobile home on Blake's Hill Ro 3 After five heartless days of cold rain, at last the sun appears, and Swenda lies on the beach at Ogunquit picking up the tan she knows her friends at home expect to see and talk about when she returns, so they won't have to talk even obliquely about the "wedding night," which would embarrass the girls, who all know that she is now ten weeks pregnant and has been "doing it" with Chuck in his Tempest since Christmas Eve, which really didn't bother anyone then but now for reasons Swenda can't understand embarrasses everyone who knows she is pregnant and had to 4 After another night at the hotel bar talking to the hookers, Chuck wakes and his hangover glues his body to the bed, while Swenda, on the beach since 5 In the breakfast nook of their mobile home, Chuck is patiently explaining to Swenda: "It's only the rational thing to do, now that you've had the miscarriage and we can finally be honest with each other and ourselves. We were too young, that's all, and now that you're not pregnant anymore, we can decide freely if we want to stay married, and honestly, honey, of course I still love you, that's not the question, because I wouldn't have asked you to marry me if I hadn't thought you were pregnant and all. Besides, we're still young and have our whole lives before us, like they say, though I'm not saying we should get a divorce or anything, you understand, but maybe if I was in the air force for four years, when I got out we'd know for sure if we wanted to stay married or not, and in the meantime you can live here in the trailer and have my support check from the air force and whatever you make off your cake decorating and, you know, we could find out about ourselves a little more, and that way we could be sure of how we felt towards each other without being forced int 6 "Oh my Christ, my good God, my sweet Jesus Christ, I don't know what we're going to do now! It's all over, all gone, everything's turned to shit!" Swenda wails, as Chuck grimly, silently, kicks at the blackened wreckage of their home. (The intensity of the fire melted the refrigerator of the mobile home of Charles and Swenda LaBas, shown at right with refrigerator. The LaBases are recent newlyweds who had lived here for only two 7 months ago, seen here cheerfully posing at the door of the "Chalet" model mobile home minutes after it had been delivered by the Bide-a-Wile Home Corp., remember, honey? 8 "How could things get so complicated so fast? I feel old." "I thought it would be easy to love me. I thought the hard part would be loving you. It would have been simple if I had been all right or else all wrong. I feel old, too." 9 We'll be all right together. I'll be head repairman in a year. My father's a happy man and your father is, too, aren't they? My mother is a happy woman, too, and your mother's a good cook. Many things make many people happy, why not the two of us? So this is life. Oh Jesus. We'll be all right together. I want to have a baby, Chuck. I hope he looks like you did. I hope he looks like you did. I want you to have my baby. This time it'll mean something. We'll just save our pennies. I'll try out for the Players. I'll be head repairman in a year. We'll be as happy as we can be. America is a wonderful place to be young and in love with love. We were kids. Now we're grownups, so this time it'll mean something. I don't understand the darkness that seemed to surround us then. I'll be head repairman in a year. I'm glad I didn't join the air force. Your cakes are the talk of the town. So this is a happy marriage. We'll be all right together, you, me and the baby, a family now. My cakes are the talk of the town. I'm glad you didn't join the air force. So this is life. It's not bad. I still wonder about the darkness that seemed to surround us then. We were kids then. Now we're grownups. Now we've got kids of our own, and here they are. The one on the right

Thank you, Mr. Banks.