Things Have Always Been Worse And Things Can Always Get Worse Too

The circle remains unbroken, but that doesn't mean we stop trying to break it.

no wonder why we lost the battle,

the counter culture can’t count.

— Eyedea, “Burn Fetish,”

In early January of 1929, less than 10 months before Wall Street would ruin tens of millions of lives, something dark and vast occurred which presaged the decade of bitter and deadly labor wars to come. At dawn, 32,000 men from across the country amassed at the gates of the Ford Motor Plant in Dearborn, Michigan, bracing against subzero temperatures for a chance to become a Ford employee. They “were given a faintly sinister presence by the eerie glow from interior factory lights filtered through blue-tinted windows and the pulsing foundry and blast furnace fires of the largest industrial complex in the world,” historian T.H. Watkins writes in The Hungry Years.

What they got was a grim human lottery. Burly hiring agents stood at the plant's gate, letting in the first ten men, dismissing the following ten, letting in the next ten, and so on, a bleak assembly-line process that continued, hour after hour. When fights broke out among men jostling for position at the front of the mass, Ford's security guards turned fire hoses on them. Drenched and miserable, men collapsed from exhaustion, exposure, and hypothermia; some were taken to local hospitals…

The mass of the writhing crowd, a city-sized population come looking for work, stokes a critical question. “If prosperity ruled the nation, as virtually every industrialist, banker, merchant, politician, financier, educator, and churchman in the land had been trumpeting for most of the decade,” Watkins writes, “— if this country was doing so well, why was it that 32,000 men needed work so badly that they had been willing to travel many thousands of miles by whatever means they could and suffer misery and the risk of death in order to find it?”

History is unbroken. That scene in Dearborn, nearly one hundred years ago, that astonishing picture of human desperation amongst supposed prosperity, remains right outside our doors. The inherent structures of capitalism — its manufactured precarity and want, its ceaseless, lecherous quest for growth, its inhuman maxim of commoditization — has ridden over the earth and left us battered, broken, riven in its tracks. It is tempting to think that our current conditions are uniquely trying, the worst they’ve ever been. While every time has its peculiarities it’s true, we do ourselves no favors by exceptionalizing ourselves. Though our time is now fast running out, “spinning so fast, we may as well be standing still,” the Salvage Collective writes, where the “rubble of the left’s defeats reaches to the retreating ice” of the Artic, where capitalism has “finally produced enough diggers” to dig its own grave, “but in doing so it ensured all that was left to inherit was the graveyard,” we do still have time yet, I submit, not merely for reflection, not only for digging, but for creation. If we more clearly connect ourselves to what our movements for justice have faced before, we can find, not a crystal ball, not a charted course, but the precious and fragile human inspiration for change that comes from realizing that people like you and me once stood face to face with the same dangers we are facing now, and some of them lived to talk about it.

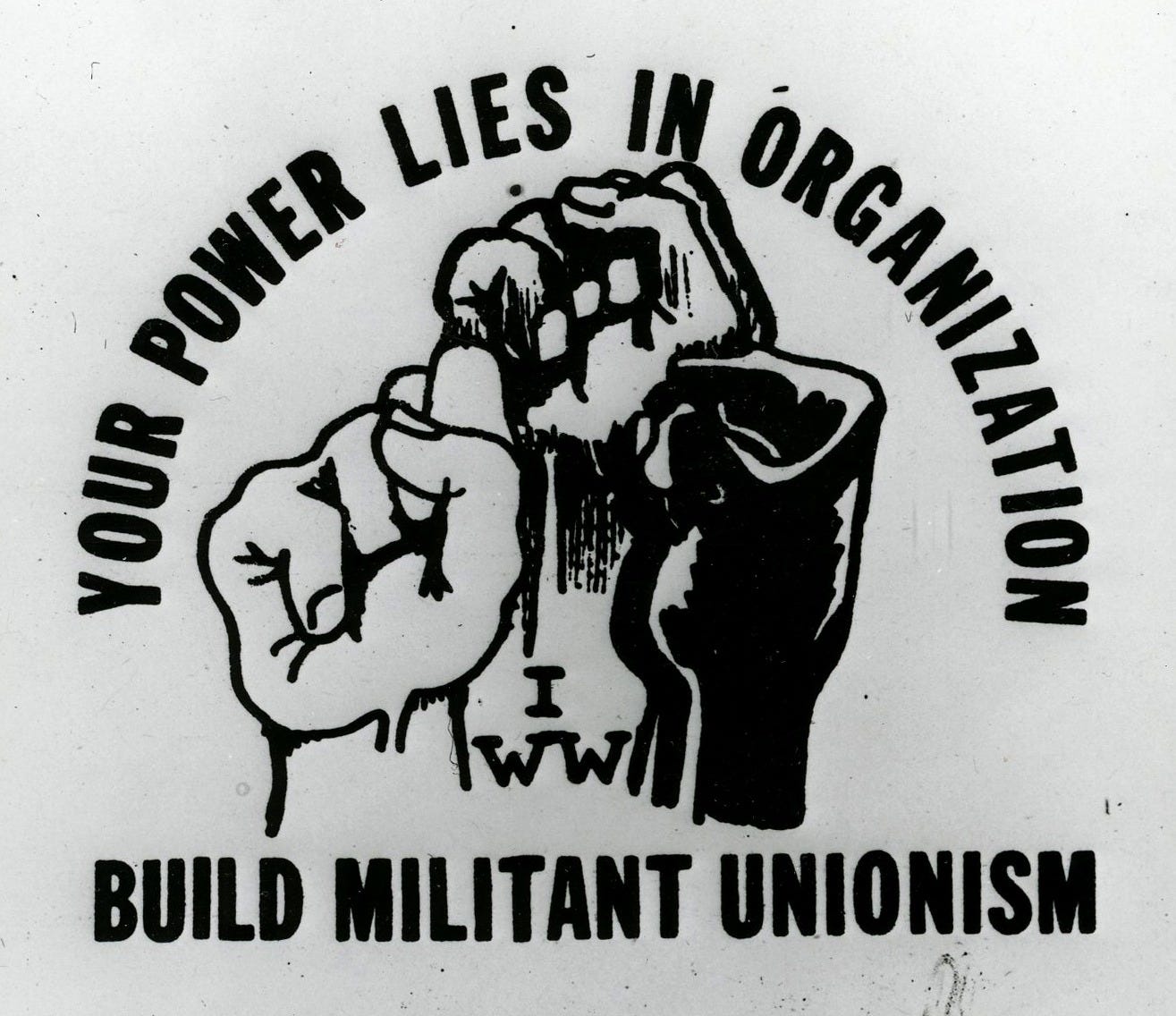

Today, the prospect of mass deportations carried out by the marriage of government and privately deputized security forces has once again reared its ugly head. I say again, because in the WWI era, tens of thousands of people were arrested, thousands imprisoned, and hundreds were deported across the country by Woodrow Wilson’s government and the many private citizens, mostly military veterans and retired cops, who joined the American Protective League (APL) to wash away unpatriotic agitators, labor organizers, conscientious objectors, and simple immigrants — or “hyphenated Americans” as Wilson put it. Now, the APL has been replaced by ICE and Erik Prince’s Blackwater; the radical Wobblies have been replaced by pro-Palestine activists. Anarchist Jews and Italians have been replaced by Mexican and Guatemalan agricultural workers and labor leaders.

I think it fair to say that things were worse during WWI. The vigilante APL was started by U.S. veterans of the horrid Philippine War, who prowled the country looking for any and all anti-war subversives. It was given the imprimatur of the nascent FBI and participated in break-ins, surveillance, arrests, and lynchings throughout the U.S. They literally waterboarded coal miners who tried to start a union and admitted it. “In the [Philippine] Islands, we done exactly the same thing,” one of them said. After the war, the Department of Justice raided hundred of offices of socialist groups, particularly the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) — the “Wobblies.” Organizers of bail funds for those arrested were also targeted. One prison defense fund in Sacramento was raided seven times in six months. “When one of its members, Theodora Pollak, produced bail for some Wobbly defendants, the police took the money, arrested her, forced her through the medical exam usually performed on prostitutes, and jailed her,” writes historian Adam Hochschild. Today, a bail fund in Atlanta, Georgia that was supporting Stop Cop City activists against charges of domestic terrorism was raided by a SWAT team with their guns drawn.

In the Ford Motor Plant those tens of thousands of men were clamoring to enter in 1929, labor conditions were deteriorating. “Ford’s security force — which was euphemistically called the Service Department — used an elaborate spy system that monitored everything from production performance to bathroom breaks,” Watkins writes, “with an especially close watch out for anything that might smack of union agitation. Troublemakers were summarily fired, and if they objected too strenuously, were seized and escorted from the premises by [a] gang of ubiquitous strong-arm men.” The parallels here to the much-publicized conditions in today’s Amazon warehouses and amongst its delivery drivers are obvious. Despite the odds, Amazon workers have achieved their first union. But many workplaces continue to languish un-unionized or even vote against unionization (after much union busting by the company of course). The manufactured precarity of capitalism keeps these workers begging for more and accepting the scraps. Meanwhile, Jeff Bezos keeps taking celebrities to space.

Capitalists are the greatest mobilizers in the U.S. today and long before now. All they have to say is “We’re hiring!” and like magic hundreds of thousands fall to their knees beckoning at the gates hoping for a Golden Ticket. This is part of what we mean when we say that the left is out-organized and out-gunned. What leftist leader today could say we’re gathering outside the factory, not to beg for jobs but to seize the means of production, and honestly hope to put up the same kind of numbers as a Henry Ford or a Jeff Bezos? The ruling class is indeed cloistered and protected from the world in many ways save for this: the astonishing displays of obsequiousness thrown their way by the people and our ostensibly democratic institutions. Presented with such evidence, the billionaire’s bloated sense of self-importance is not entirely irrational. As Watkins writes about Henry Ford and those 32,000 men standing outside his gates:

The scene that greeted Ford as he arrives at the River Rouge plant this January morning, then, probably gave him considerable satisfaction. The extraordinary number of men huddled in the cold and freezing slush of the car park under the lowering clouds, elbowing and fighting one another and the hiring agents to become one of those selected, shivering violently in the terrible blasts from fire hoses when they got too restive — for him, the very number of such men could only have validated the power of the magic he had given the nation.

It is our task to change the structures of the society which not only allow for this kind of exploitation, but which make that exploitation rational. Our task is tall. “The strongest weapon against revolution, or any hankering for it,” China Miéville writes, “isn’t positive but negative: it’s not any claim that the world in which we live is good enough, but that capitalist-realist common sense that it’s impossible, even laughable, to struggle or hope for change.” This capitalist realism, as Mark Fisher formulated it, goes hand in hand with the common apathy, complacency, and cynicism already so endemic to the American spirit. “We were not the country of free speech or free press or free assembly,” historian Gilbert Seldes wrote of the early years of the Great Depression, “we were not the country of the rights of labor; we were not free of religious prejudice; we were not interested in social justice…we heard of starvation wages and child labor and barbarous cruelty in chain gangs as if these were natural episodes in the brilliant newsreel of our lives. So long as they passed quickly, they did not matter.”

Though the society today is growing again more disillusioned with capitalism, we are a long ways away from abolishing its structures. No one has been spared from its reaches. Even those who have “dropped out” of the society to try their own alternatives are living only in fleeting bubbles floating in between otherwise embattled communities. All of us are forced to endure the constant usurpation of our ways of life so that we may be commodified and extracted from but a little bit more. These regular transformations are “neither at the behest nor for the benefit of those at its sharp end,” Miéville writes. “It’s no wonder that modern life is rubbish, generative of anxiety, deracination, a deep psychic as well as economic instability, not to say disempowerment and death, for millions.”

As a good leftist, I say all this not to scold those within my own class who are just trying to get by, nor to demoralize ardent leftwing organizers, but rather to offer a realistic appraisal of the environment from which we must move out of, and thereby define the means by which we will do so. There is no place to begin except from where we are, and where we are is dismal. Dispiriting though this may be, it is also clarifying. It allows us, if we are able, to slough away illusion, idealism, and the liberal frame of mind that tells us that progress and justice are simply inevitable, devoid of the ugliness of struggle, sacrifice, and courage. They are not. Remember that American slavery was around for longer than it hasn’t been. That great evil, inspiring of “a nameless, haunting dread that never left the South and never ceased,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, seemed eternal — until it wasn’t. Its abolition required bloodshed beyond compare. Of the few Americans who understood slavery as the central American problem, “fewer still were willing to fight it as they knew it should be fought,” said Du Bois. “They had known it a hundred years. Yet they shrank and trembled.”

We should not be afraid of struggle, of rebellion, of revolution, but rather their opposite, our enervating existence under capitalism. “Rebellion is only an occasional reaction to suffering in human history,” historian Howard Zinn wrote.

Measure the number of peasant insurrections against centuries of serfdom in Europe — the millennia of landlordism in the East; match the number of slave revolts in America with the record of those millions who went through their lifetimes of toil without outward protest. What we should be most concerned about is not some natural tendency towards violent uprising, but rather the inclination of people, faced with an overwhelming environment, to submit to it.

If we are to move out of this condition, we must make a careful, correct, clear-headed analysis of the facts as they are. Otherwise, we will make potentially devastating strategic, tactical, and political mistakes that could set us back even further than we are today — and even cost people their lives. Mahmoud Salem, an Egyptian blogger who helped spur the Arab Spring protests in his country — which contained both the rapturously beautiful community at Tahrir Square and the unmitigating authoritarian hell that is Egypt today — has lived to regret that he encouraged an uprising that did not have a progressive organization behind it that was ready to direct it towards a better society. “[H]e never wants anyone to feel the guilt that he does,” journalist Vincent Bevins writes in If We Burn, “the knowledge that he asked teenage boys to risk their lives and watched them die, only for the entire movement to experience defeat. When trying to do something as difficult as changing society, there are no guarantees that anything will go as it should.”

The western left, bruised and battered, divorced from the best of its history, and without a unifying banner under which we all can devote our energies, has already debilitated itself for far too long with undisciplined, alienating rhetoric which is in fact counterrevolutionary. I am sympathetic to our disorganized plight, which in many ways was imposed upon us by the highly coordinated destruction of our movements and the murders of our best leaders for the past century and a half. Pieces of my heart fall away whenever I read the accounts from those on the left who witnessed the breaking of their movements, their communities, all that they worked for their whole lives. From Rosa Luxemburg to Emma Goldman to Richard Wright to George Orwell to Eugene V. Debs to “Big Bill” Haywood to Al Richmond to scores of others, the story of the left is, seemingly most of the time, a story of heartbreak, loss, and bafflement. “Among the left diaspora, despair, mental illness and suicide are not uncommon,” Miéville writes about the years preceding the Russian Revolution. “Prigara, a starving, deranged veteran of the Moscow barricades,” spoke to his friend Lenin “‘excitedly and incoherently about chariots filled with sheaves of corn and beautiful girls standing in the chariots.’ … Prigara escapes the protections of his comrades, ties stones to his feet and neck and walks into the Seine.”

Self-annihilation from within the left is of course attended by regular annihilation from without. In the U.S., after unwelcome anti-capitalist elements in the country had been obliterated by Woodrow Wilson, Hochschild writes about anarchist labor organizer Emma Goldman returning to what remained of her life’s work after these purges:

Finally Goldman arrived in New York, her home, where she “found destroyed what we had slowly built up through a long period of years.” [Postmaster General] Albert Burleson had shut down the magazine she edited, and her long-time collaborator Alexander Berkman, also just released from prison, was waking up in cold sweats at night. He had spent more than seven months in solitary confinement, part of it in a two-and-a-half-foot by four-and-a-half-foot punishment cell, for protesting the killing of a Black convict shot in the back by a guard. “The large sums of money raised while we were in prison…had gone for appeals in cases of conscientious objectors, in the political-amnesty activities, and in other work,” Goldman wrote. “We had nothing left, neither literature, money, nor even a home. The war tornado had swept the slate clean.”

The closest a socialist candidate for president ever got to the White House was in Eugene V. Debs, who was imprisoned for speeches he gave against America’s entry into “The Great War.” He nevertheless garnered one million votes in the election while sitting in a jail cell. “By the time Debs died in 1926,” Hochschild writes, “the [Socialist Party] that had once elected 33 state legislators, 79 mayors, and well over 1,000 city council members and other municipal officials had shrunk to less than 10,000 members nationwide.”

Though I admire Gavrilo Princip’s gumption in assassinating Franz Ferdinand, what the status of the American left could have been had the senseless mass slaughter that followed Princip’s gunshots not occurred is an alluring hypothetical. As Hochschild writes:

The Socialist Party [and the Industrial Workers of the World] would never recover from the mass jailings and the crushing of its press that took place under Wilson. Had it not been so hobbled, even with a minority of voters, it might well have pushed the mainstream parties into creating the sort of stronger social safety net and national health insurance systems that people take for granted in Canada and Western Europe today. This is one of American history’s most tantalizing “what if” questions.

Despite the left’s historical losses, despite our ongoing embattlements, these are no excuse to keep on making the same mistakes of liberal scolding and individuated action. There is no power, none, in being right about the world. You must also be political, which is to say you must be serious, which is to say you must deal with the world as it is, which is to know that if you want to change society for the better you must make considered calculations about what you will prioritize, what you won’t prioritize, and, critically, what your theory is that will get the majoritarian working-class to manifest that good society.

I have my own thoughts about how to get there, which very briefly can be summed up as: Leninism and democratic hierarchical organizations are effective at consolidating power; whether you think we should slowly amass a series of major reforms that will get us to the good society eventually, or go instead for an all out revolution, both of these routes require immense power and rigorously prioritizing certain issues above others. As Bevins notes in If We Burn, “Even within the very radical Marxist-Leninist tradition, the concept of revolutionary ‘retreat’ is important. Winning all at once — that is Hollywood. There is a right way to lose, there is a right way to wait, and there is an effective way to regroup. … Given the complexity of the world’s problems at the moment, there is no reason to believe that victory is right around the corner, no matter one’s idea of triumph.”

There are questions and contradictions in the society which cannot be resolved without first resolving others. We must be on the same page about what these are, even as we know that there are a great many things that must be changed. Abolitionist John Brown “thought that there was an indefinite number of wrongs to right before society would be what it should be,” one of his compatriots wrote, “but that in our country slavery was the 'sum of all villainies,' and its abolition the first essential work.” And Brown marched, into the ages, with that critical understanding. Today, our greatest evil is globalized capitalism. We must, as Du Bois said about Brown’s stance against slavery, “uproot it, stem, blossom, and branch.” We must give capitalism “no quarter, exterminate it and do it now.”

You may notice that the seeming nadirs I lay out here often preceded an explosion that shot the society back upwards. Three years after those 32,000 men came begging for work at the Ford plant, a socialist-led hunger march was brought onto those very same grounds to demand an end to the degrading surveillance system, “a reduction in the speed of production, a seven-hour day, and the right to organize,” Watkins writes. About three thousand men made their way to the factory gates.

Tear gas was fired, but the wind swirled it around in ragged clouds that enveloped marchers and policemen alike. The marchers answered by pelting the police with rocks and pieces of frozen mud. … firemen began spraying the crowd with water from fire hoses. … [Ford’s security officer Harry] Bennett jumped out of his automobile and confronted the nearest man who appeared to be a leader of the increasingly wet and swiftly freezing marchers. Bennett was almost immediately struck on the head by a large piece of slag that had been thrown. As he fell, bleeding copiously, he dragged the marcher, [Young Communist League] leader Joseph York, down with him. When York managed to disentangle himself from Bennett and stand up, machine-gun fire broke out from the overpass and cut him down, then rippled through the rest of the crowd, sending it scattering. Four men, including the twenty-two-year-old York and a sixteen-year-old boy, were killed, and more than sixty marchers wounded and otherwise injured.

Over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American workers battled through the deadliest labor wars in the Western world. “The working folks have walked bare handed against clubs, gas bombs, billys, blackjacks, saps, knucks, machine guns, and log chains,” Woody Guthrie wrote, “and they sang their way through the whole dirty mess.” The New Deal era, buoyed by a radical, muscular labor movement that used the strike to get workers what is rightfully theirs, gestured toward a better society which has been steadily pushed further and further away from our grasp by the power of capital. When I look at the history of our movements, their sublime successes and sapping failures, I see that, as Miéville writes, these moments of “hope and lament, utopia and apocalypse, are inextricable.”

We are living in revolutionary times. The tinder is there. Matches are being lit every day. These facts should strike fear into your heart because as I look around it’s mighty plain to see that those who stand in the wings best poised to make the most out of this revolutionary moment are not on our side. As one drunk, pissed off Puerto Rican man said to me recently while staring into my eyes: “I love the left. But the left has no initiative. It’s powerless. The right are more willing to die and kill for their beliefs. They’re willing to shed blood. They’re willing to defend their families. The left isn’t there yet. I just see a lot of flag waving, but no action. … The right has all the guns. You will be disemboweled by people that disagree with you. Y’all be dead. They’re gonna shave your head, put you in a camp, make you eat crackers, and that’s how you’re gonna die. I’d rather die before that happens to me.”

The alternative to this grim revelation? Organize, organize, organize.

It is our duty as those who want to change the world to begin only from where we are, not from where we’d like to be. This, I know, is infinitely frustrating and difficult, and the ranks of those on the left who have lost faith, or secluded into strictly academic questions, or adopted the seductive, deadening, arms-length language of meme-ified online leftist patter, or succumbed in the most irrevocable way to despair could fill oceans and bibles and graveyards and dusty card catalogues and long-ago effaced monuments from better, more noble, more romantic times. But here we are. The end of history will never arrive so we cannot wait for it. The ordinary, hard, constant, thankless work of getting your class comrades to move together is what faces us then, now, and always. This fight is not in vain, we’ve got a world to gain.

Very good, but what would replace capitalism right now? It seems some hybridized form is more like it. Then we’ll see how that goes, and maybe after that it changes into something else, on and on