Yes, Language Is Important, But Changing Words Does Not Change Material Conditions

A spade is a spade is a spade.

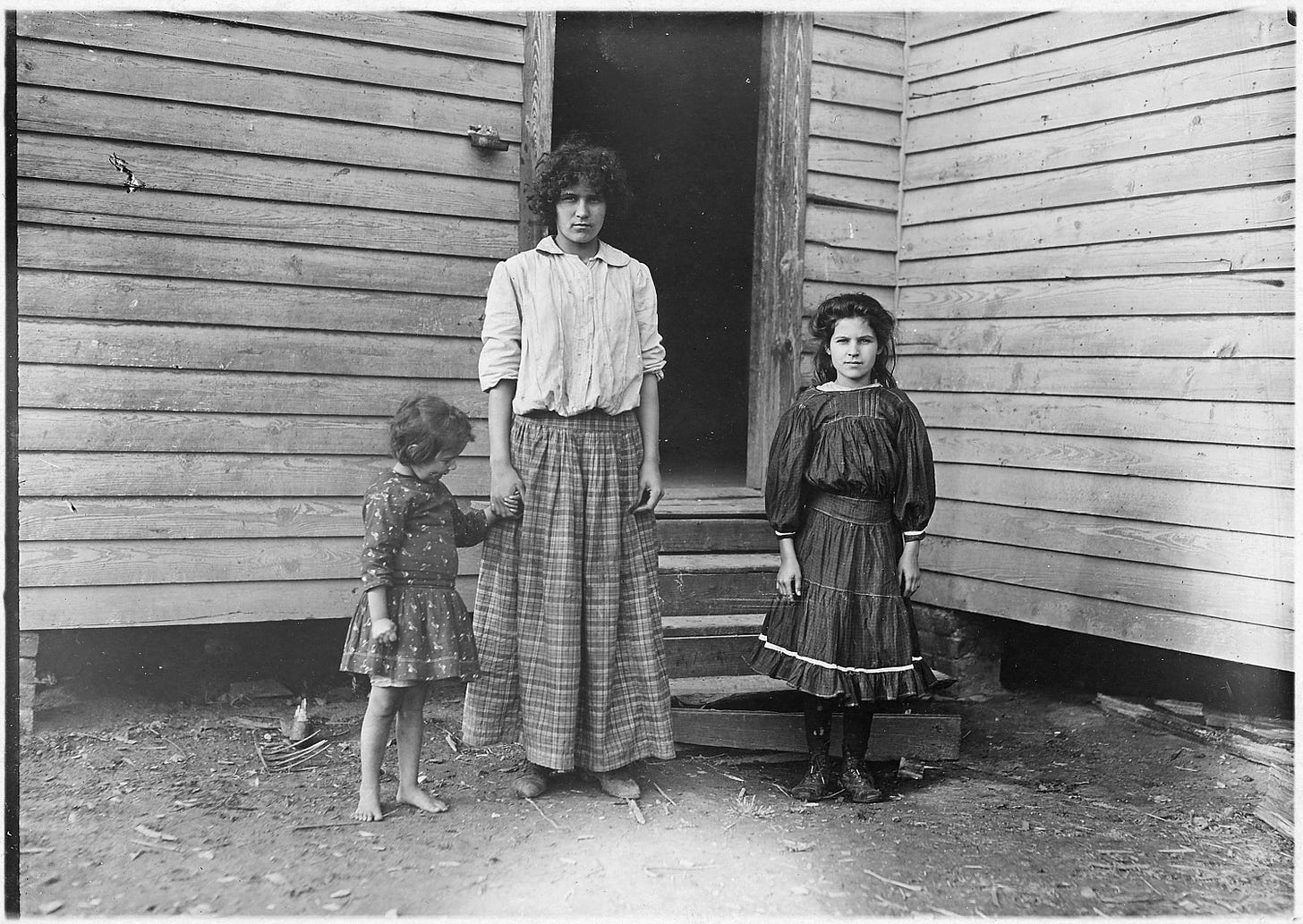

Look at this picture:

The original caption for this photograph reads: “Curtis Stiner, an example of the mountain farmer of East Tennessee. ‘I love my mountains, and I want to stay right here the rest of my life if I can.’ The flooding of the reservoir area will take his home, October 1933”.

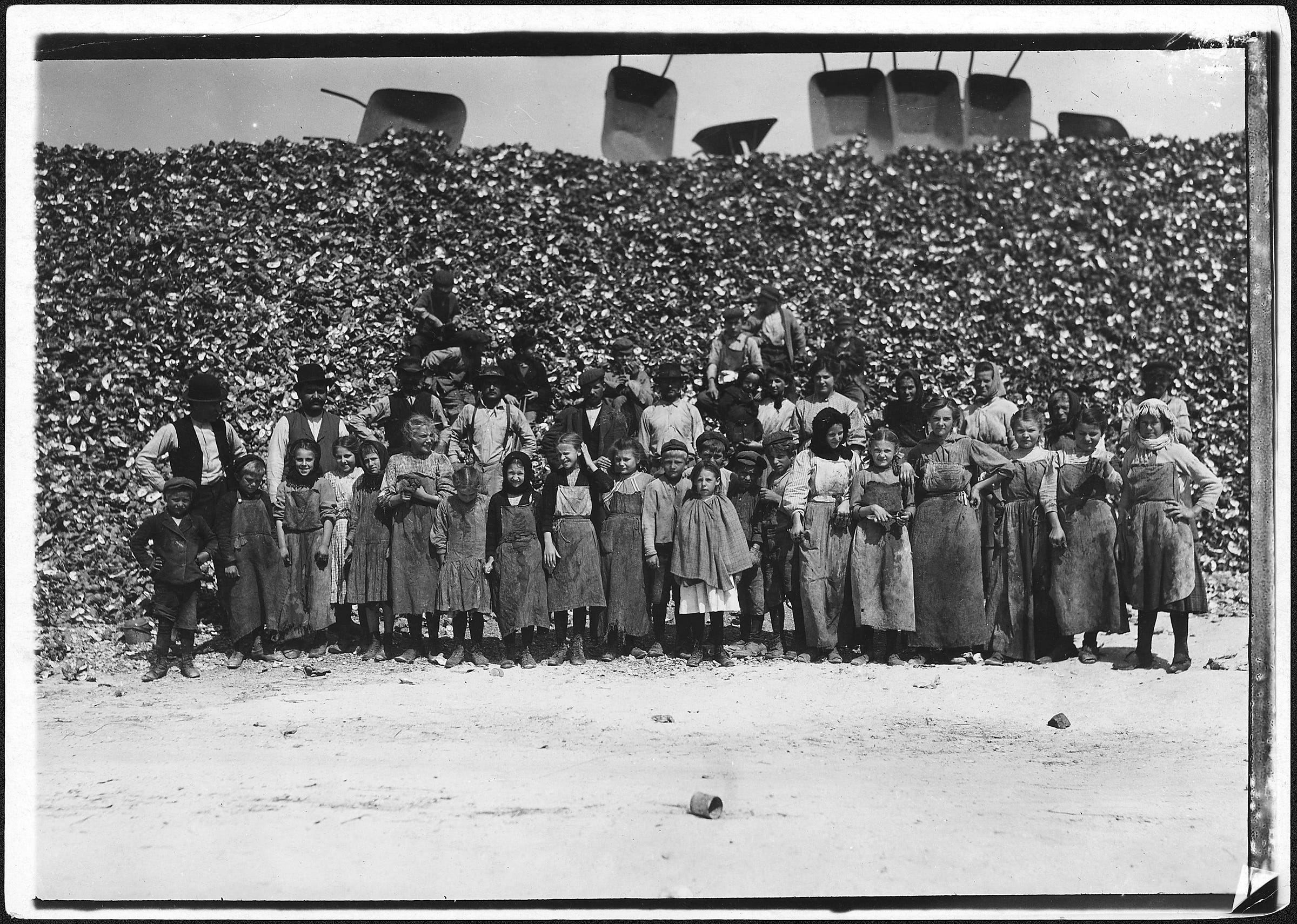

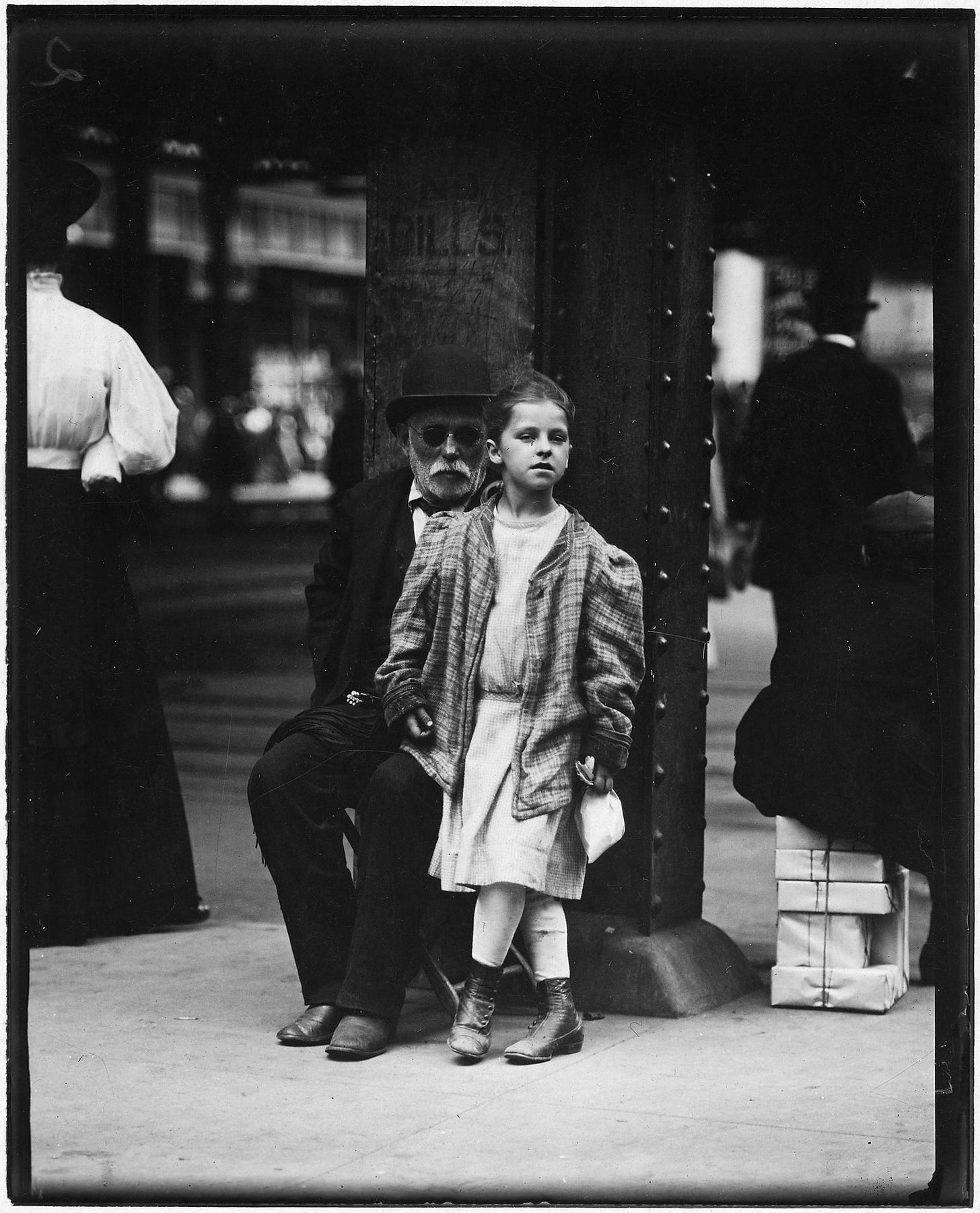

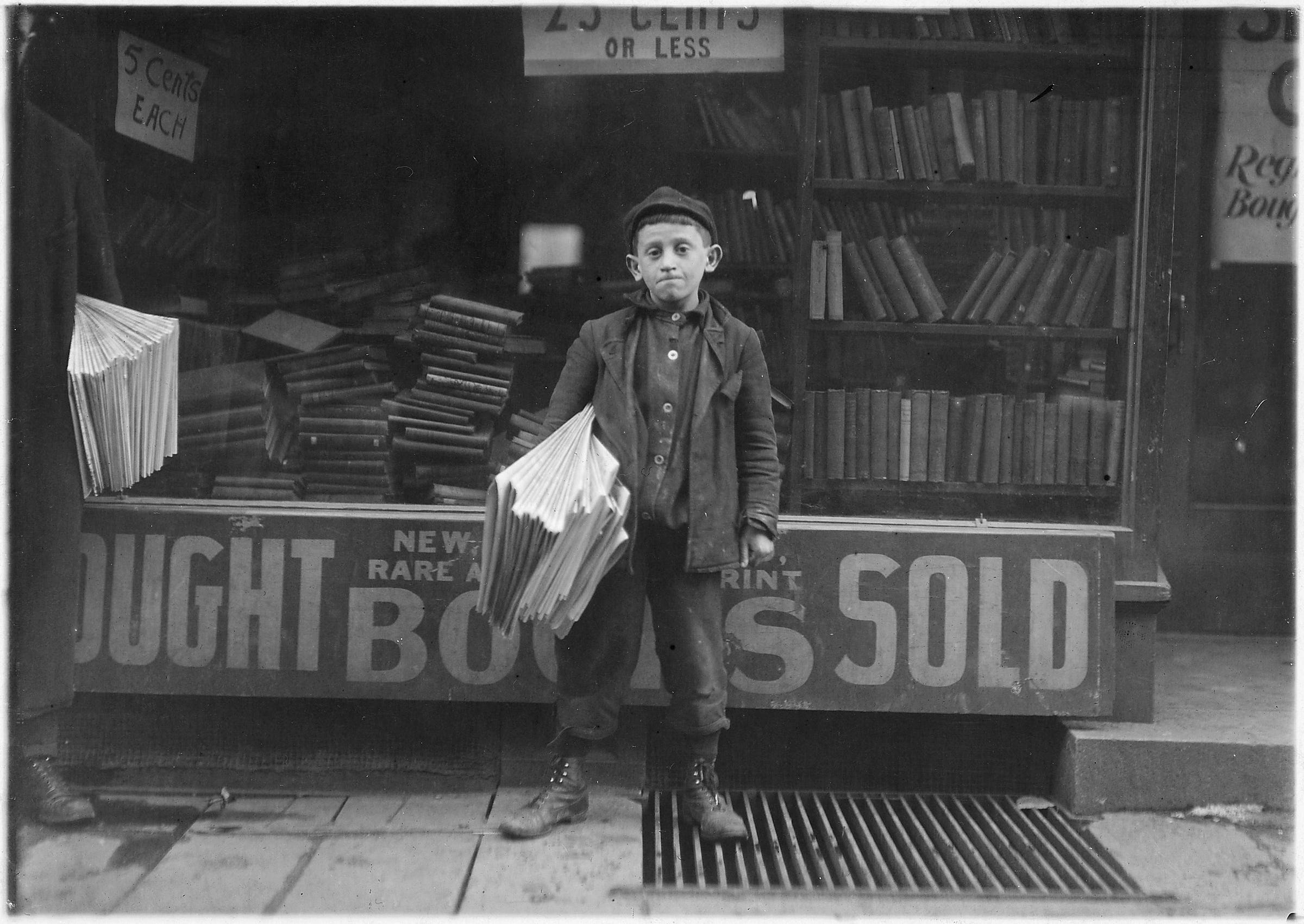

The photographer, Lewis Hine, took most of his pictures as part of the Works Progress Administration — the same project which produced the immortal Depression-era image of the worried “Migrant Mother” in Nipomo, California by Dorothea Lange — as well as the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), a project to end child labor in the United States. To that end, Hine collected more than 5,000 photographs from all over the country documenting children working in hard, dangerous conditions in factories, mills, coal mines, produce fields, canneries, and on street corners. “For many years I have followed the procession of child workers winding through a thousand industrial communities,” Hine wrote. “I have heard their tragic stories, watched their cramped lives and seen their fruitless struggles in the industrial game where the odds are all against them.”

Now, this isn’t just an excuse to show you the work of one of my favorite documentarians. I want to call particular attention to how Hine gives a level of agency to the people he photographs, and contrast this with the problem I hint at in the title of this article. First, look closely at these pictures and read their captions:

Hine documented child labor for the NCLC from 1908-1918, a time when you couldn’t be surreptitious as a photographer. He had to take time to set up his equipment. The camera was bulky. He framed the people in his photographs with care. And, critically, the people depicted in the images often said “Yes.” They posed themselves. They faced the camera. They smiled. They scowled. They gazed. They were not mere subjects. They made their own claim as to who they were, thereby standing themselves apart from their often horrid condition. They are “able to look into the lens (or even past it) without faltering, flinching, pleading, shrinking, or cowering,” historian Kate Sampsell-Willmann writes. The “image is a meeting of […] individuals on an equal level.” The dignity afforded to the people in Hine’s photographs is what made these documents compelling at the time and it is what makes them compelling today.

Hine recorded many of the people’s names, their ages, and short quotes about themselves. He did this thousands of times. The sheer volume of these photographs is part of what gives them their power. Taken as a whole, they present a historical document that is difficult to refute and which comes as close as is possible to surviving the inevitable anonymization and befogging degradation that befalls most artifacts. This is why Hine’s work is important and must be remembered. It demands itself to be remembered. His was not a project only of propaganda or aesthetic form, but of humanization, or as close as any photographic record can so achieve. On viewing Hine’s photographs at the time, a reporter gave this reaction: “There has been no more convincing proof of the absolute necessity of reformation of the child labor laws…than these pictures showing the suffering, the degradation, the immoral influence, the utter lack of anything that is wholesome in the lives of these poor little wage earners. They speak far more eloquently than any written work — and depict a state of affairs which is terrible in its reality — terrible to encounter, terrible to admit that such things exist in civilized communities.”

Hine did not hide or pretty-up the ugly reality he sought to expose. And at the same time, he allowed the dignity that was stolen from the child laborers in their workplaces to be restored to them, however slightly, in the images. The humanity and the outrage that Hine let shine through his photographs helped to secure new legislation that outlawed child labor and thereby improved the material living conditions of millions of workers and their children around the country. As historian Alan Trachtenberg put it, Hine was able to elicit in his images “a love that wishes simultaneously to heal as it reveals.”

Now, in contrast, please, look at this:

I’m not homeless, I’m just EXPERIENCING homelessness. I’m having a homeless EXPERIENCE! I may be living out of my van, or in a tent under a bridge, people may be giving me dirty looks as I eat tuna out of a can on the sidewalk, but it’s okay, I’m just having an EXPERIENCE! It’s Van Life! It’s Jimi Hendrix and THE HOMELESS EXPERIENCE, man! Come share in this EXPERIENCE with me. Can I use this experience on my resume?

How does this help homelessness? What material conditions change by simply changing the words?

Now look, I too wince at calling myself homeless (even though some people would say that I technically fit that description) for the same reasons that I wince at calling myself queer (even though some people would say that I technically fit that description): because these are identity markers that I myself don’t really identify with and they tend to reduce someone’s humanity to that single identity. I always try to keep such terms at an arm’s length because, you know, there is no such thing as an identity. So in some sense, I understand why “person experiencing homelessness” is in fashion now. One nonprofit says that they “use the phrase ‘experiencing homelessness’ because of the many children, youth, and parents who have told us that homelessness is something that happened to them — it does not define them. It is something they went through, it is not who they are.” This is absolutely true. There is a way that calling someone homeless essentializes them to that identity, just as any other identity marker has the power to do — white, black, gay, trans, drug addict, whatever. Getting people to think in terms of systems as opposed to individual problems is generally good politics. If the term “experiencing homelessness” helps people to understand that they, too, could become homeless at any time, that they could one day be that homeless person through no fault of their own, if it helps people to empathize better with just a little shift in vocabulary, then great! But, this doesn’t really change any material conditions, does it? Whether someone is hungry or “food insecure” doesn’t change the fact that, even with the total institutionalization of the food bank nonprofit industrial complex, millions of people in this country are malnourished.

I ask again, how does this linguistic change actually help homelessness? I don’t care if you call me homeless, houseless, unsheltered, someone doing “van life” (if you want to be needlessly cute about it), someone “experiencing” homelessness (if you want me to laugh at you), a wandering soul (gross), a free spirit (I’ve gotten this multiple times, please stop, I’m not a hippie), a traveler, a bum, a hobo, a nomad, whatever, none of these monikers change the simple, material fact that I AM LIVING OUT OF MY FUCKING VAN, and that simple material fact changes the way that many people look at you and interact with you, consciously or not. If the word “homeless” conjures up a whole series of images and attitudes that relate to a person who is “homeless,” those images and attitudes will simply shift to any other term you’d like to use for that material condition. A rose by any other name, etc.

As I was travelling around in my van this last summer and fall, I had a few different experiences that drove home to me the ways that people will treat you differently if they think you’re homeless. These ranged from the benign to the kind to the odious. In Minneapolis, I was sitting in the back of my van, side door open, my feet on the curb, eating some canned tuna (mixed with tapenade and good quality Californian olive oil, thank you very much) with crackers out of a bowl. A young couple walked by me. A moment later the woman came back up to me and said, “Excuse me, sir, I live nearby, could I bring you some food?” This was the first instance I noticed of someone treating me differently. Knowing that, at least economically, I was not at all in dire straits, and therefore feeling quite undeserving, but also feeling like it was just a simple misapprehension on her part (I’m not homeless! I’m not one of them! I’m just a cheap little ragamuffin!), I responded with upturned brow and sweet voice, “Oh no, I’m okay, thank you. I have plenty.” “Okay,” she said and turned to leave. “Have a good one,” I said. And on with our days we went. Nice people in the Midwest.

Atlanta was a different story. There I parked one too many times in a neighborhood near Inman Park, a more upscale part of Atlanta just east of downtown. An older gentleman (I use the term with derision) told me I couldn’t “camp” there. I told him I wasn’t camping there, because I wasn’t. I’d only ever parked there during the day as I did work in a nearby coffeeshop and then moved to the more welcoming Five Points area to sleep for the night. But he just didn’t like the look of me, I guess. “Well why don’t I just call the police and they can figure it out,” he said and immediately turned back into his house. It was not lost on me that I was in Atlanta to help protest the construction of a $90 million police training facility, and now some old rich white dude here was perfectly willing to at least threaten me with a police encounter. This is what we call a douchebag. My next notable interaction in Atlanta as a newly minted homeless person was much more pleasant, if a little weird.

John Dingus is his name. Yes, really, that’s his real name. He’s a homeless man who has been in the Atlanta area for a long time now. He was probably in his forties, a little sun-kissed, a little sweaty. He was also a little crazy, like a lot of chronically homeless people I’ve chatted with, but in a generally coherent and interesting kind of way. We met on a section of the Beltline, a pedestrian path through the east side of the city near the Fourth Ward skatepark. I’d seen him practicing the same tune every day on one of the many upright pianos that were set up along the path. He came up to me one evening when I was playing one of those pianos and asked if he could share the tune with me, something that he wrote. It was a nice piece — kind of classical, kind of melancholy. After he played it, he asked if he could recite some of his poetry for me. Absolutely, I said. It was good poetry. It had a cadence and it rhymed and it was very anti-establishment, right up my alley. He then looked at me, squinted his eyes, and said, “You homeless?” Oh no, I thought, now even the homeless people are starting to think I’m homeless. I laughed a little uncomfortably and told him I was staying in my car. “So you probably don’t have much money to spare,” he said. He explained that he usually asks someone if they’d be willing to spare something if they think his poetry is worth it. He told me he was really hungry. “My friend stole my money from me. I was supposed to buy my girlfriend something. She’s in Minnesota. Now she’s mad at me cause I couldn’t get it,” he said. I told him I could bring him some food the next day, which I did. He seemed genuinely surprised and very appreciative when I showed up that morning with a bag full of groceries (paid with food stamps) from a nearby co-op. He then pulled out his smartphone (something I’ll never get used to seeing a homeless person have) and showed me some videos he’d made of his poetry. One of the poems is called “Just My Luck,” which reads partially:

as society chooses to look at homeless men and women with sour looks on their face, are we not even worried about the fate of the human race? ... just my luck, that mankind won’t help someone blind across the street, I mean, fuck, I’m on the streets, but, brothers and sisters, I still help another brother down on his luck to something to eat. so please, where is our humanity, so to speak?

Amen, Brother John (Dingus). Amen.

I share these stories just to say, yes, I get it. Homeless people face “sour looks” and everything else that goes along with that. I’m not making any kind of personal claim to the homeless experience because I just really don’t think I’m in the same boat. But I understand the desire to humanize people, and some people think that changing terms can change attitudes and thus maybe change material conditions. But I’m trying to argue that that really doesn’t follow.

Changing words does not help people. Improving material conditions helps people. You can argue (and I do) that improving material conditions for people requires the advancement of certain ideas (I argue for socialist ideas), and ideas are composed of words. So yes, words matter. “The future of this world depends on to what extent, and by what means, we liberate ourselves from a vocabulary which now cannot bear the weight of reality,” James Baldwin once said (but he did not mean by “vocabulary” a mere glossary of terms). If our ideas cannot stand the “unwavering, unflickering brightness” of reality, as W.E.B. Du Bois put it, then those ideas must be changed. And we can go about that process of change, partially, by choosing our words carefully. But going from homeless to houseless, insane to mentally ill, mentally disabled to mentally spicy (give me a goddamn break), debilitatingly autistic to neuro-divergent, a piece of shit to problematic, suggests to me a set of ideas that wish to pervert reality in order to comport with an illusory liberal ideology that serves to — what, exactly? Soften the edges of a sharply decaying society? Smother me with a nice down pillow instead of strangling me with a rough hemp rope? These aren’t humanizing words, they are words of absolution. “Poor people used to live in slums! Now the economically disadvantaged occupy substandard housing in the inner cities,” George Carlin said. “Smug, greedy, well-fed white people have invented a language to conceal their sins, it’s as simple as that.”

This is a problem because it’s trying to put a positive spin on things which are absolutely not positive. George Orwell wrote in 1946 about how political language is used chiefly to obfuscate:

Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.

This is what soft language does. It hides reality. When I hear the term “neuro-divergent,” I don’t think of the mentally disabled. I think of a painfully awkward Gen-Z alternative type person who doesn’t like to leave their house, can’t maintain a consistent conversation with someone, can’t keep proper eye contact, and who has found a new pet term to ascribe to themselves to make them feel special and “valid.” The problem with terms like neuro-divergent is that they do not humanize the actual human outliers of our society — they disappear them. These terms hide the very people who are in most need of humanization. A dangerous schizophrenic person, a nonverbal autistic person who can’t control themselves, a bipolar person in the throes of psychosis, these people are not cutely “neuro-divergent.” They are disabled in a very negative way, their disability negatively affects the people around them, and they need as much care, support, and human understanding as our society can manage. When you try to put a positive spin on these conditions by lumping them all under the sunshine-and-rainbows term of neuro-divergent, by putting little personality quirks on the same footing as profound mental disabilities, by trying to normalize the abnormal, you undercut any material project that seeks to actually remedy these ills for what they are — ills.

To put it better than I can, the writer Fredrik deBoer describes his experience of working with a nonverbal autistic child at an elementary school. DeBoer spoke to the child’s mother about raising him. He writes:

She was really not a fan of the autism awareness community of the time. This was well before the “neurodiversity” movement and all of its habits. It was all about awareness, raising awareness, 5ks for awareness, bumper stickers for awareness. That was precisely what angered her the most. She said to me once, “What does awareness do for my kid? How does it help me?” ... It was a good question, one I couldn’t answer. Today I don’t hear about awareness so much, but there’s still plenty of the basic disease of awareness thinking - the notion that what people who deal with a particular disability need is a vague positivity, that what every disabled person requires is the laurel of strangers condescendingly wishing them the best. Now, with the rise of neurodiversity and the notion that autism is only different, not worse, we are confronted with similar questions. When a mother struggles every day to care for someone who will likely never be able to care for himself, what value could it hold for her that his condition is called diversity, rather than disorder? What value can it have for him, who cannot speak to comment on the difference?

And there is another, more odious element to these changes in language. It serves as a signifier. People who use the new proper words can show that they are the good people. The enlightened ones. The pious caste. And the people who haven’t caught on yet better do so quick lest they be outed as reactionary fascists who oughtta be gassed immediately. This policing of language is yet another sad example of an enforcement of cultural norms taking the place of an actual broad-based political project that fights for universal, material betterment. It is a means to cudgel people, not uplift them. It is a way to exclude anyone from a political conversation about how to actually solve material problems if they don’t use the right words. Your neighbor down the street who works in construction called homeless people “bums” and he rolls his eyes at people who use they/them pronouns so fuck him! He’s irredeemable! Even though he is your class comrade, he has no role to play in the revolution except as a deplorable reactionary to be made an example of (this seems to me to be the inevitable implication of such language policing). If your goal is to actually improve things, which requires mass movements composed of diverse sets of people (including people who don’t share your cultural signifiers), then this is just straight up bad politics! But one can argue that good politics isn’t really the goal here.

In one of the earlier prescient warnings about what would become our culture’s pervasive need to “call out” people for linguistic transgressions, Mark Fisher describes in his 2013 essay, Exiting the Vampire Castle, “This priesthood of bad conscience, this nest of pious guilt-mongers, is exactly what Nietzsche predicted when he said that something worse than Christianity was already on the way. Now, here it is…” Fisher’s essay should be grappled with by everyone, particularly on the left, because these over ten years since he wrote it, things largely remain the same. Fisher asks “why would capital be concerned about a ‘left’ that replaces class politics with a moralising individualism, and that, far from building solidarity, spreads fear and insecurity?” Though Fisher’s essay slides a bit into esoterica for anyone not already immersed in a leftwing milieu (I have no idea what he means by “libidinal-discursive configurations”), he is nevertheless refreshingly clear and direct with his basic argument:

The bourgeois-identitarian left [meaning self-righteous liberals and scolding leftists] knows how to propagate guilt and conduct a witch hunt, but it doesn’t know how to make converts. But that, after all, is not the point. The aim is not to popularise a leftist position, or to win people over to it, but to remain in a position of elite superiority, but now with class superiority redoubled by moral superiority too. ‘How dare you talk – it’s we who speak for those who suffer!’

I provide these examples for your consideration without comment:

Why is this our state of affairs? My preferred theory is that internecine warfare such as this happens when any political project is ruthlessly suppressed and defeated for generations, as it has been for the left in the United States. Failure breeds desperation breeds recrimination breeds attrition breeds disorganization and so on. Combine this with a highly commercialized, individualized neoliberal society — what UC Berkeley professor Wendy Brown calls an age of nihilism and hyper-politicization — and you’re gonna get some really sick, dysfunctional pathologies such as these. As writer Amber A’Lee Frost diagnoses it:

[O]ur fellow anti-capitalists betray us all by enjoying or creating the wrong art, reading the wrong articles, championing the wrong theories, or even laughing at the wrong jokes. The left is at once flailing and sclerotic. Afflicted by a vague autoimmune disorder, we cannot even retain what little power we have, nor do we have any institutions capable of doing so; thus, we are able to smack only those within arm’s reach of us—ourselves. Meanwhile, the bigger and stronger the right gets, the more insular we become, single-mindedly obsessed with purifying our own ranks and weeding out the problematic among us.

This is not politics. It is anti-politics. And, it must be said, as I so often do: this is nothing new. The particular details and contours will always be unique to their time, of course. But this phenomenon itself has been seen time and again. In the feminist movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s, Jo Freeman called it “trashing:”

What is "trashing," this colloquial term that expresses so much, yet explains so little? It is not disagreement; it is not conflict; it is not opposition. These are perfectly ordinary phenomena which, when engaged in mutually, honestly, and not excessively, are necessary to keep an organism or organization healthy and active. Trashing is a particularly vicious form of character assassination which amounts to psychological rape. It is manipulative, dishonest, and excessive. It is occasionally disguised by the rhetoric of honest conflict, or covered up by denying that any disapproval exists at all. But it is not done to expose disagreements or resolve differences. It is done to disparage and destroy.

And critically, Freeman argues that trashing, calling out, cancelling, whatever you want to call it, is “much more prevalent among those who call themselves radical than among those who don't; among those who stress personal changes than among those who stress institutional ones; among those who can see no victories short of revolution than among those who can be satisfied with smaller successes; and among those in groups with vague goals than those in groups with concrete ones.”

This is both depressing and hopeful. Depressing because the problem seems endemic to leftwing projects, hopeful because it suggests that this tendency can be alleviated with careful organization. A’Lee Frost wrote that she is “grateful for the painfully honest accounts of the now faithless” such as Freeman because they helped her “remember that the mercenary tendencies and paranoia [on the left] are most often matters of organizational dysfunction, rather than failures of people or politics.” If we who think of ourselves as progressives can look to what has worked before, to the best of our history, to the plain, common sense, universalist values that have been championed for so long by socialists all over the world, then we will understand that true solidarity and comradeship are cultivated not through petty social control, not through language and thought policing, but through clear appeals to our better natures.

Going back to the people that Lewis Hine photographed, what do I see? I see an artist of profound sensitivity concerned primarily, not with terminology (“If I could tell this story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug a camera,” Hine said), but with exposing a material reality in order to change that reality. “I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected,” Hine said. And he did — with vast, irrefutable evidence. Hine and the National Child Labor Committee didn’t preoccupy themselves with pedantic terminology. They didn’t call child laborers “children who are laborers” and correct anyone who said otherwise. They didn’t melodramatize things by saying, “Exploited innocents! Defiled cherubs! Sullied babes in the woods!” or some other such old-timey socialist rhetoric. Nor did they sterilize things with turgid nonprofit legalese like “economically disadvantaged minors” or “underage industrial human resources.” They went around the country showing people, with clear language and expressive images, the horrors of child labor. And they succeeded in helping to clamp down on its widespread practice.

We shouldn’t be trying to create a world where people refer to homeless people as “people experiencing homelessness.” We should be trying to create a world where such a material reality as homelessness is as close to impossible as possible.

You can start by throwing a few bucks my way, pal. Thank you :)

Excellent essay!