“You ain’t no kinda man if you ain’t got land.”

— Delmar, from O Brother, Where Art Thou?

In one of his final works of writing, Russell Banks tells the story of Doug Lafleur, a man who sold off the last of his family land and then lost everything. Bank’s short story, called “Nowhere Man,” collected in a posthumously published book called American Spirits, hit me hard and by surprise in a lot of ways. (I talk about many of the plot points here, so be careful if you don’t want to spoil it.)

I first discovered Banks’ writing my sophomore year of high school in a collection of short stories called Success Stories, which I wrote about in an obituary of Banks here. So it feels meaningful to me to have his last book be another short story collection, in a way the closing of a circle. Like that previous book, Banks uses the device of having a throughline tie the stories together in one way or another. With American Spirits, Banks simply sets all of the stories in and around the small community called Sam Dent somewhere in upstate New York, which he has used in previous novels such as The Sweet Hereafter. If Stephen King’s universe has Pennywise the Clown and Cujo rampaging through small-town Maine, Banks has incorrigible alcoholics named Doug wasting their sad lives away in the Adirondack foothills of Sam Dent.

What felt revelatory to me in high school about reading Banks’ stories was that they revealed and gave voice to a world, or a way of looking at our world, that was, not cynical exactly, but deeply understanding and empathetic of all the ways in which we are irrevocably ground up by the threshing machine that is this life, that catastrophe is always just around the corner, and even when that catastrophe arrives, neither damnation nor deliverance may follow, life just keeps going, and going, humdrum, with or without us, whether we want it to or not, and that we really try to be good to the people in our lives even if we fucking hate them sometimes, and how utterly destabilizing it can be to our best efforts to keep that prepared pleasant face up for the ones we care about the most when someone simply asks you, “Do you really love me?”

These kinds of ideas that I found in Banks’ work at the time, as well as primarily in the delightfully dour music of The National, were fun explorations for me as a teenager, lacking any real connection to my actual experience, and therefore were escapist in their own downbeat way. These days, with more life lived, good and bad, sometimes even rapturously sublime and interminably hellish, Banks’ work hits discomfortingly too close to home. “If we don’t find one way to hurt ourselves,” he writes, “we’ll find another.”

Damn.

So in the story we meet Doug Lafleur, the titular “Nowhere Man,” a married man in his mid-thirties with three young children who rarely leaves the town he was born in and spends most of his free time at the local tavern making a fool of himself. He also likes to hunt on his father’s land and wants to bring up his son to learn the ways of firearm use and animal tracking the same way his father showed him out in their family woods. But with not much in the way of good-paying work and with a young family to take care of, Doug and his sisters decide to sell off the large property that had been in their family for generations — “all 320 acres. It was the last large tract of undeveloped forested land inside the town limits,” Banks writes. The Lafleurs sell it to a stout and stern out-of-towner named Yuri Zingerman from New Jersey. “He said he wanted it for a private hunting preserve, but promised Doug that he and [his brothers-in-law] Roy and Dave could continue to hunt on the property. Zingerman said he was a veteran of the IDF, the Israel Defense Forces, but he talked with a regular American accent.”

This arrangement where Doug and his family can continue to hunt on the land is alright for a bit, but things start to descend very low very fast. Zingerman one day decides he doesn’t want the Lafleurs going onto his property anymore, and informs Doug about this at the bar in an interaction which swiftly turns into a physical altercation where Doug is humiliated by Zingerman’s military martial arts training in front of his own wife. This is just one of the many daily humiliations Doug is subjected to. His regular summer job is working as a handyman, mostly for the summer tourists, “fixing their broken faucets, cutting brush, splitting and stacking firewood for their custom-made brook-stone fireplaces, reshingling roofs of their guest quarters, lugging their trash and recyclables to the town dump, through it all trying to feel less like a servant than a local woodsman helping inept city folks adapt to a rural environment.”

But it is Zingerman ripping away Doug’s god-given right to traipse through those woods that really unmoors him, ultimately irrevocably. It was Zingerman’s “particular, thwarting use of Doug’s father’s and grandfather’s land that made Zingerman Doug’s enemy. It felt of a piece with the many forms of oppression and discrimination that afflicted him and made him feel small, weak, and childlike, made him think of himself as dumb and ignorant.”

Shortly after being informed by Zingerman that Doug’s family can’t go onto the property anymore, Doug decides to defy him and take his son Max on his first hunting trip anyway, along with the two brothers-in-law, to find themselves a buck or two to take back home. “He can go straight to hell if he thinks I’m not hunting on Pop’s land,” Doug says.

It’s here, sitting in the snow with Max near the deer’s bedding patch waiting for the buck to return with its doe and fawns, that Doug reflects on the meaning of this land to him:

Before [his grandfather bought the land], before the American settlers and the British and the French Canadians and the Dutch, for ten thousand years it was the Mohawks’ and Mi’Kmaqs’ home ground. Doug likes thinking about that. He liked calling up that long line of woodsmen and hunters. He liked to believe that he was descended from them, that his relation to this piece of the earth matched theirs, that he knew in all seasons its streams and brooks and swamps, its glacial forests changing from hardwoods to dark conifers to ferny sunlit patches, that he knew it fully as well as those old-time hunters did, and he knew the man-made trails and paths laid down over centuries on top of the trails and paths followed for millennia by the animals before humans made their way here, and he knew the behavior and habits and needs and desires of all the animals and birds that lived in the forest.

These and other passages really spoke to me, and it’s here that I introduce some of my own family story to explain some of the reasons why Banks’ story is so impactful.

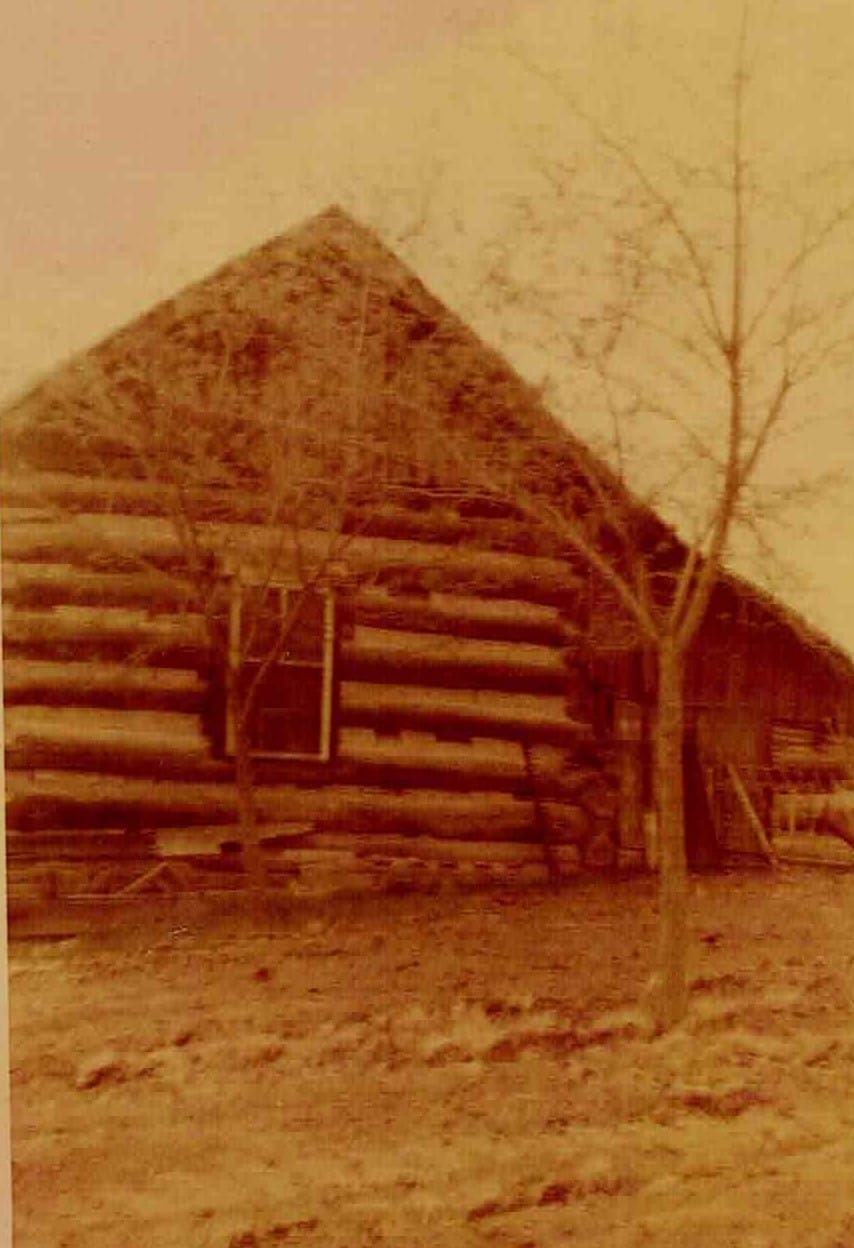

One side of my family was raised out on “the ranch” in rural California, with a contingent of them having homesteaded on land near Pozo back in 1882 where they built a two-room log cabin. That cabin, built with a mix of digger pine, hard oak, and adobe, and later expanded to four rooms, was still standing (though leaning) less than 10 years ago — 134 years old. Generations of the family lived and died out there. My great-great-great grandfather — born in the 1700s — is buried on a hill out there behind the ranch house. Both my great-great grandparents and grandparents are buried in the family plot on the other side of the house.

My grandfather built a “new” house next to the original log cabin, and it looks and feels like the kind of house built singlehandedly by a man with no formal training in construction. He added many ramshackle additions to it over the decades without any regard or knowledge about modern construction codes, but it is sturdy, cozy, and home all the same. That house and that land, 160 acres of it, was where I spent a fair amount of my childhood, listening to stories from my family about their lives spent on the ranch and what it meant to them. Raising the cows, the horses, the pigs, the lambs, the chickens, and the (dreaded) turkeys. Keeping the grass down. Shooting deer and coyotes and birds and rodents and snakes. Shooting each other with BB guns. Dodging those deer and cattle on the winding country roads. A trip into town was a big day. Drinking from natural springs and collecting rainwater. Collecting Native American arrowheads and mortars and pestles. Finding fossils from a long-ago sea. Sleeping outside. Sitting in grammar school in the one-room schoolhouse. Going to Sunday School. Burying family members died of gangrene or a rotten tooth or from working under their car or from just plain old age at the dinner table. The land was mostly hard and dry and not good for growing much but high enough that every once in a rare while snow would fall.

My grandfather, who I technically met but never knew since he died when I was only 3 weeks old, spent his whole life out there. His father died when he was only 13 and so he found himself with the responsibility of taking care of his mother and his four younger siblings out there. He knew the land, just as Doug Lafleur in Banks’ story did. My uncle wrote about my grandfather, his dad:

I believe hunting Black Mountain on the forest reserve [the Los Padres National Forest], was his favorite place to go… He knew every likely spot to find an old buck, every feeding area and every spring where they could get water. He had names for every canyon and spring. The Forest Service used some of his place names when they built their maps, but many of his place identifications have been replaced on the maps but remain in our memories. When the Forest Service decided to improve and develop some springs to provide more consistent and usable water sources, they had Daddy show them the springs he knew so well. As part of this effort they developed and renamed the spring he called Third Canyon. It became Milburn Spring on their official maps. Other spring names that come to mind include Willow, Milk Can, Sulphur, Goat, and Deer. All of the names had a reason or commemorated an event.

My grandfather took his children out hunting and showed them how to dress and butcher a deer for venison jerky, just like Doug Lafleur does. Banks writes:

Doug was down on his knees sawing through the deer’s leg bones below the dewclaws, leaving the hide still attached. “Watch, now,” he said to Max. “This is how you make a slouch pouch.”

Max said, “Why’s it called a slouch pouch?”

Roy laughed and said, “Nobody except your dad calls it that. He made it up himself.”

Doug then proceeds to tie the strips of pelt from the deer’s legs together to turn them into backpack straps of a kind, carrying the eviscerated deer over his shoulders. My uncle tells a similar story about my grandpa:

Daddy developed a method for packing a deer on his back. It is far easier to pack a dead weight than to drag it like most hunters try to do. He would cut a slit in the skin of each leg between the knee and hoof. Then he would remove the leg bone, leaving the hoof attached to the strip of skin. Next the right foreleg is tied together with the left back leg. The hoof keeps the knot from slipping. The left foreleg is likewise attached to the right back leg. He could then carry the deer like a backpack, the legs serving as shoulder straps. The head would have to be held in one hand to keep it from flopping around, his rifle in the other hand. …

On one occasion, Daddy had killed 2 deer on the back side of Black Mountain from the ranch. He would carry one deer till he got tired. Then, he would “rest” while walking back to where the other one lay. He would pick up the second deer and head for home, leap-frogging past the first one. When he got tired he would drop the second deer and go back for the first. He continued this process until he finally got home. That must have been one LONG day, and I’ll bet he thought twice before again shooting two deer on the same day on the backside of that mountain.

The ranch has always felt to me quite separate from the world, especially now more than ever. It’s quiet. It’s relatively secluded. The house itself doesn’t have much modern amenities or decorations. Having a gas stove and running toilets out there is really living high on the hog. The old wood-fired stove behemoth is still in the house. The A. B. Chase pump organ from the late 1800s is still there, having a marvelous earthy sound, though in need of serious repair. The house feels old because it is old. It looks old. It smells old. It sounds old. One of the main associations I have with the ranch is the sound of ticking clocks, because there are no other sounds to hear out there. That side of my family feels old-fashioned. They’re staid, they’re hard working, they’re modest. They have a very particular way of talking, or not talking. One of the hallmarks of our family get-togethers is that even when we’re all in the same room there will eventually be extended lulls in the conversation, and then the ticking clocks come back in. The word parochial is generally regarded as a pejorative but I use it in a strictly positive sense to describe the feeling of being out there, of sharing the time with the family, of its simplicity and warmth. Perhaps pastoral is a better word. But its separateness is the key. Which is why it feels like such a profound violation when the modern world encroaches on the ranch.

Making the drive out to the ranch now, passing the various bedraggled properties dotting the sides of the road, you can see Trump flags and associated regalia imposing itself. This feels…..so…..wrong. Never mind my particular leftist politics. Left or right, the displaying of any politician’s swag out there in the arcadian country, this place that always felt of its own time, hits me as being deeply out of touch with the land out there. It’s like some young dude coming to the local square dance and stopping the flow of all the happy dancing old people to yell “No cops! No KKK! No fascist USA!” Yeah, alright, cool dude, I’m down, but that’s not what we’re here for. “Fuck you, abolish the police!” Okay, are you trying to instigate a revolution right here, right now, at the Elks Lodge? Between the promenades and the do-si-do’s? Or are you just brandishing your sloganeering virtues like an asshole?

This is hard because I’m not one of those people who thinks that politics and religion should never be discussed amongst mixed company. That’s how you get a compliant, illiterate population. I’m trying not to make this argument sound like special pleading on my behalf. Which for me means that it comes back to the context of the land. How dare you desecrate this place with something, not political, but so crudely modern. If nothing else, it’s anachronistic.

Likewise, in Banks’ story, Zingerman turns Doug Lafleur’s land into a training ground for preppers, Oath Keepers, militiamen, Proud Boys, and the like — disempowered masculine men looking to flex the only kind of power they could ever envision with their small, grotesque, impoverished imaginations. “Middle-aged White men with stubbled beards disabling scary strangers who looked like the young Osama bin Laden with jujitsu or karate or whatever Israeli martial art Zingerman was teaching, and the muscular men in tight sleeveless tees, … pulling a concealed pistol from a quick-draw holster and crouching and pretending to spray a windowless cinderblock room with bullets, instantly killing bodyguards and family members who happen to be off-camera and are presumed to be armed and dangerous, wearing explosive vests.”

Doug himself is a big fan of Trump and guns, but Zingerman’s use of his father’s land in this way is a step too far. If nothing else, it’s just plain noisy. Similarly, my family has always had guns, always used guns, but never have I seen anyone in the family fetishize guns. It was never an identity. Guns were used for hunting meat, killing pests, and the odd-target practice of tin cans and glass bottles. Gun etiquette was taught and enforced. Guns are tools, not playthings. Being profligate with your ammunition for fun was not encouraged. To see people treat guns otherwise, as markers of identity and virtue, or as mere uncareful toys, reads to me as a severe character flaw.

My own feelings of violation in this regard are why this passage from Banks’ story hit me:

This was before strangers every weekend started driving past the house on their way to Zingerman’s, most of them in SUVs and pickups with out-of-state plates, some flying Confederate flags, their bumpers and tailgates plastered with stickers promoting gun rights and libertarian slogans like Don’t Tread on Me and Live Free or Die and Christian references to apocalyptic biblical verses. This was before the automatic weapons and the explosions, when it was still possible to hunt the property and kill a deer. “There was a time,” Doug says, “when we had peace and quiet in abundance around here. When private property meant privacy. When a Dead End sign meant you didn’t see down-state and out-of-state jerks driving SUVs and pickups past the house day and night and ORVs and ATVs trashing the woods and trails and scaring off the game.”

What I deeply appreciate about my family’s ranch, the land, the stories of the people from that time, sitting in the tiny church with the kindly old people, scratching in the dirt, is that it all feels like it has a simple dignity to it. It was a self-sufficient and satisfied community. It was small. It was close. It was old-timey. It was everything that our decadent modern world is not. Doug Lafleur had something like that. Because Doug lost any power that he had over that land when he signed the papers, his impotent resentment can only grow. He tries to hold on, irrationally, to anything that he can, to whatever can anchor him. “It’ll always be Pop’s,” Doug tells his wife. “Just like it’ll always be Grand-pop’s. That’s why people call it Lafleur’s Woods.”

We too hold onto our names for things. One petty example: My family has always called a nearby area southeast of the ranch Carissa Plains. And it is Carissa Plains, damn it! Not the more Spanish-sounding Carrizo Plains, the preferred pronunciation used by all the fuckin out-of-town student biologists and professors at the local university who take regular field trips out there to study and document the steadily declining flora and fauna (seriously, all the species are disappearing, shit is bleak). I’ll remind you that the Spaniards did their own raping and genociding, so their claim to the name of the plain is tarnished just as mine. And I do admit that it’s nice to know my family name graces a spring mapped by the Forest Service. But without our hold on that land, so what? “Hey! Did you know there’s a spring in the middle of nowhere named after my family?” Cool, dude.

We hold onto names, and for what? Without the land, without the deed, the names mean nothing. We’ll be gone one day and our children will forget most of what we told them and so will their children and no one will remember that we were a part of this land like it was a part of us, that we set down and named it and called it ours, this thing that gave us the dust of our dust, and to which we happily returned.

And look, I know I’m speaking from a position that is partly occluded, that is partly unearned nostalgia. I wasn’t there in “the old days,” I only hear about them from those who were, and they have their own nostalgias too. But having been partially raised out at the ranch for at least some years, I know that the surroundings feel different now. Yet still, I know this is all irrational. I know it is. I’m not talking about reason. I’m talking about land. The earth itself. Without it, we really are nothing. And so it is for Doug Lafleur. If he hadn’t sold his family’s land to Zingerman, this crack-pot hypermasculine Israeli Defense Forces-loving ethnic-cleansing douchebag, then “he’d still be able to hunt on his ancestors’ land. This love of the land, this irrational claim on it, was Doug’s strength, and it was his weakness.”

It is indeed an irrational claim. In some sense, all the land everywhere all over the world is everyone’s. It cares not for our petty claims on it and any people can make a life on it. How dare you try to own the very eternal rock and sand and soil beneath your degrading feet. What a farce. To call it yours is to exclude not only the living but the dead, all those who walked this earth before your silly little life came along. But also, in another sense, the land that we know is the land that we love. The places that we come from, that supported us, that first cast light unto our eyes, that held us closest to the ground as we could ever be held, those places will always have us. So of course we are right to make some kind of claim on them. Even if it doesn’t say so on paper, that land is ours, it belongs to us sure as we belong to it, forever.

“That sonofabitch Zingerman, he can have his hunting camp out there if he wants,” Doug says, “he paid for that right, but he can’t keep me from tramping across those ridges and creeks that I know like the lines of my own hand and killing a deer once a year and busting up a few coveys of partridges and quails. It’s my goddamn birthright.”

Well, Zingerman does just that.

In a confrontation where Zingerman discovers Doug and his son Max and his two brothers-in-law returning from their hunting on Zingerman’s land, Zingerman forces them to drop the dressed deer and their guns at gunpoint. He then takes the deer on the back of his truck and makes them all watch him drive back and forth over their prized family firearms, destroying them. This violation begins the long degradation of the Lafleurs, unmoored now from their traditions. “It was the last time Max, who was then eleven, went hunting with his father and uncles, who eventually replaced their guns with lesser rifles from Walmart and altered their annual deer season rituals by driving out of town to hunt on fallow or abandoned, uncultivated land…, mostly open fields crisscrossed by creek-bed thatches of cottonwood and willow, land more suitable for bird hunting than for deer. They each found and shot a buck on those fields, easy shots, almost as if they were hunting semidomesticated deer in a game preserve. But their deep woods deer-hunting days seemed to be over…”

Doug at first finds an animating cause in his resentment for Zingerman, which of course has nothing but a negative impact on his wife and children. Later, with not much left to do, the drink takes hold, and his meaning is lost. Banks writes:

Without that ancient connection to the land, who was Doug Lafleur, anyhow? No one. Nothin. Just a not very talented amateur musician hanging around this small town for a lifetime, finding easy ways to house and feed his wife and kids and spending too much time at the local tavern amusing his neighbors with tall tales and dumb songs, a man with no good reason to be living and working here instead of somewhere else. Christ, anywhere. And no matter where he lived and worked, wouldn’t it be the same? A nowhere man, that’s what he’d become.

I must also admit, if by some calamity I knew that I no longer had a connection with the ranch, no longer had the ability to go there whenever I wanted and walk wherever I pleased, I would be totally untethered. As long as it’s there, I have somewhere to go. For Doug, he cannot survive without the land.

When faced with the end of your way of life, as Doug was, madness ensues. The Native American tribes, forced from their lands, relentlessly hounded to near extinction, had their Ghost Dance, the magical thinking in the face of assured obliteration that the tribes, united, could summon forth their spirit ancestors, joining them in the fight against westward expansion, putting a stop to the insane hubristic Manifest Destiny once and for all, and thus restore their traditional, ancient, and essential connection to the land. This apocalyptic movement instead lead to a final death of the warrior Native Americans, driving them underground or making a last run for cover, clutching their children’s bodies, bodies ripped through by repeater cartridges, the shrapnel from canon fire, choking on their blood, their hundreds and hundreds of bodies dumped and frozen together in common ditches dug by civilized white men with shovels and guns in the cold wet earth of Wounded Knee, at last joining those old ancestors they believed would save them in the year 1890, just eight years after my family settled near Pozo.

This is all of growing interest to me, maybe because I’m just getting older. I wrote a poem recently, one of my favorite things I’ve written, dedicated to the children of Gaza that connects my Italian/Polish family’s roots being torn out of Sunnyvale, California by Silicon Valley tech bros and weapons manufacturers to the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Another of my proudest poems, “They Will Not Return,” is about the ruination of a family by a company that forced the father to participate in its project of mercilessly extracting resources from the land. Now, obviously, middle-class families being uprooted by Google and Northrup Grumman and having their fruit orchards clear-cut is not quite the same thing as the generations-long project of ethnically cleansing the Palestinians by the apartheid state of Israel, nor is it the same thing as the wholesale genocide of Native Americans. To equate them is absurd, but that is not the idea. The idea is that all of these things are indeed part of the same project of colonial capitalism, a towering human folly, the greatest evil we have ever known. Silicon Valley happily gives its technology over to Zionists so they may murder entire families in drone strikes. The Northrup Grumman facilities supply the munitions. General Atomics supplies the drones. They keep the war crimes going. Our fruit trees and their olive groves just get in the way so they must be destroyed. Our land on both sides of my family has been desecrated not only by the shallow vulgarities of partisan politics, those embarrassing, garish displays of prideful bumper stickers and idolatrous sun-bleached flags waving in front yards, but also in service of the worst crimes imaginable — the extermination of entire peoples and indeed of all life. These are the machines of genocide, running smoothly, right here on our land.

With “our” land, I don’t mean the private acquisition of acreage passed down from one generation to the next, delineated and fenced off, named and commodified, a concept laughably alien to the peoples who lived here for tens of thousands of years before us. I mean our land as in the land that each and every one of us has a responsibility to — the soil, the rocks, the water, the orchards and the farms, the glaciers and the oceans, every plant and animal, all over the world, for these are humanity’s lifeblood, our only means of survival, our hope and our purpose, the things that will keep us here and tied, if we choose.

There is a critical moment in “Nowhere Man,” which I won’t share here, where Doug’s life and the life of his family could have gone another way. Where there could have been some kind of redemption, even if only pyrrhic. And really, that moment, as with so much in life, was ultimately controlled only by fate. Doug’s choices may have gotten him to that moment, but they wouldn’t get him out. Fate could have gone another way for them. But it didn’t. The land was taken from them, and would always remain so.

At the end of Bank’s story, Doug drives home one night after another bout of heavy drinking at the tavern. He swerves off the road, hits a tree, and is killed. His wife sells their remaining acreage to Zingerman, and she and the kids move far away. Zingerman demolishes their house. And that’s the end of Doug Lafleur.

I know it’s irrational. But I can’t let this land go. The alternative may very well be ruin.

Stunning writing, thank you. I'd love to see your extended thoughts on Banks' 'Lost Memory of Skin'.

Wonderfully written Kody. Love this.